Forget estimates, start with appetite

Why starting with time constraints makes better products

What if the secret to shipping faster wasn't better estimates, but throwing estimates out the window entirely?

I was flipping through Shape Up recently,

's book about how 37signals builds and ships product. Like all useful systems, it has an opinion. Ryan isn't trying to create a comprehensive Bible for every development team. Shape Up begins with a worldview. It explores what it means to build things, how we define problems, how we shape and share context, and how to balance top-down control with engineering freedom.It doesn't prescribe a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, it provides a flexible model for understanding the interdependent forces in product teams: customers, resources, time, technology, and people.

The "Shape Up system" contains dozens of useful ideas for product teams, things like:

Shaping teams and processes

6-week cycles

The "betting table"

Breadboards and fat marker sketches

Hill charts

Cool downs

...and more

A host of interesting tools, each meant to integrate with the others. But there's nothing stopping a team from adopting individual components and folding them into an existing workflow. One need not adopt it root-and-branch to see enormous benefits.

The book deserves a future deep dive on why it's such an effective and desirable way to build for most practitioners. But I want to focus on my favorite tool from the Shape Up arsenal: defining the appetite.

The problem with traditional scoping

We're all familiar with estimates and scopes. We sit down and describe something we like to build, then we start with "how long/how much will it take to build this?" In a typical scoping process, a PM takes a big collection of requirements, then consults with engineers and designersto determine how long the project will take. We start with an overprescribed solution, and try to solve for too many unknowns up front.

This way of defining work is upstream of so many of the issues that plague product teams. Slowness of shipping, bad customer fit, quality and stability — these are inevitable outcomes of a poorly-defined starting point.

Appetite: the inversion that changes everything

Setting the appetite inverts estimation process. In Ryan's words:

Estimates start with a design and end with a number. Appetites start with a number and end with a design. We use the appetite as a creative constraint on the design process.

Lets say our product is a SaaS for project time tracking. Customers want a way to create subprojects underneath top level projects, organized by customer. We investigate the technical needs to build it and determine that, as-defined, it'll take 4 months. With all the changes needed to front-end, our mobile app, and database migrations, it's quite involved.

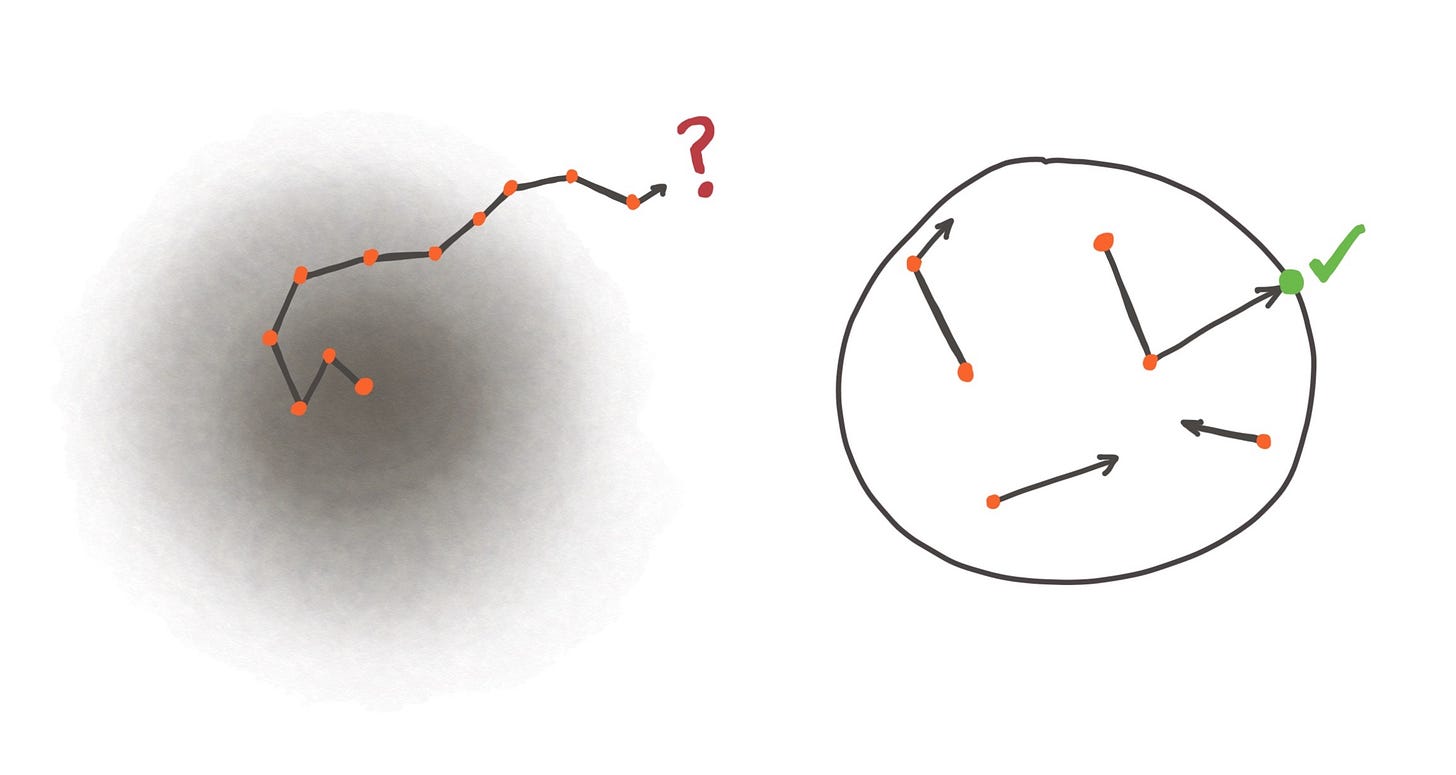

Rather than begin with a detailed spec and expect an estimate, we should work backwards. Instead of "we want this. how long?", we should ask ourselves "we have 6 weeks, what can we accomplish toward this objective in that window?"

Rather than define a richly-detailed design of what we want, appetite requires us to start with a problem definition, and refine that first. If we narrow the problem down, we also narrow the solution space. Solutions are allowed to be smaller and more focused.

The appetite starts with time boundary and works backward to a design that fits inside.

Appetites define sound and acceptable constraints up front. And constraints are wonderful tools for generating creativity.

Constraints create better solutions

Teams often have constraints that are too few and too wide. It may seem counterintuitive to start out a project wanting less time and fewer resources. But if we use appetite correctly, we allow ourselves the freedom to mold our requirements to fit within the box.

On the other extreme from "how long will this take?", you'll sometimes encounter the hard ask for a specific thing, with a command to get it done. This is a constraint, but not a useful one. It's certainly not an appetite.

Setting appetite is a conversation: a back-and-forth between leadership, product, design, and engineering. We debate and discuss the relative merits of each detail, its value, its feasibility. We horse-trade toward a rough target that feels achievable within the appetite boundary. It feels doable, yet also worthwhile. The thing we decide we can finish in the 6-week window must also be worth its 6-week cost.

We can only judge what is a "good" solution in the context of how much time we want to spend and how important it is.

The appetite box forces us to crystallize both problem and solution, giving us a clear picture of the destination from the starting line.

Freedom within boundaries

Initially, the constraint feels limiting. But chosen wisely through proper shaping, constraint becomes freedom. Well-shaped work with understood appetite helps designers and engineers spend their time and expertise where it's highest-leverage.

This is the implementation of the "hard edges, soft middle" approach: define the boundaries teams must stay within, but permit exploration within those limits. Shaped work tells us what we're doing, and equally important, what we're not doing.

Capping the downside

Shape Up incorporates value judgment and puts caps on downside risk.

When you work in batches, with 6-week cycles and work shaped to fit within, you also put caps on the downside risk of failure. If we approach the end of our cycle and it's evident we went off-course, misestimated, or found out our users don't really care as much as we thought, the most we lose is 6 weeks.

Constrast this with the common failure case, where we started with a 6-month scope in pursuit of the big idea. When we hit the end of that half-year, the bad news creeps up on us. We're looking at 6 months down the drain. The news is so bad that the team doesn't want to admit it. We keep chasing the finish date to get it shipped, even though we know it won't work and customers won't care. The sunk cost fallacy bears its ugly mug and compels us throw good money after bad, or to face the music.

The appetite advantage

The appetite approach doesn't just improve planning and execution. It fundamentally changes how we think about problems and solutions. By starting with time and working backward to design, we're forced to clarify what really matters. We strip away nice-to-haves and focus on essentials.

This isn't settling for less. It's discovering what "enough" looks like when we're honest about constraints.

Whether you adopt full Shape Up methodology or simply borrow the appetite idea, the underlying principle remains powerful: embrace the constraint, define the boundary, then let creativity flourish within it.

Your team will ship faster, your stakeholders will have clearer expectations, and your customers will get solutions that actually solve their problems rather than over-engineered monuments to unchecked ambition. Sometimes the best way forward isn't to ask "how do we build everything we want?" but rather "what's the most valuable thing we can build with what we have?"